.gif)

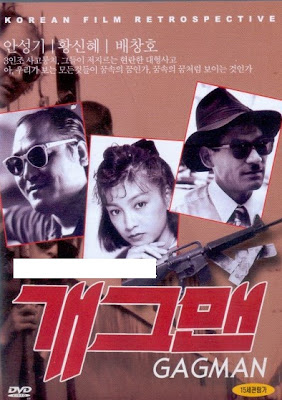

Gagman. 1988. Directed by Lee Myung-se. Written by Lee Myung-se and Bae Chang-ho. Produced by Lee Tae-won. Cinematography by Yoo Young-kil. Edited by Kim Hyun. Art direction by To Yon-gu. Music by Kim Su-cheol. Sound by Lee Young-gil.

Cast: Ahn Sung-ki (Lee Jong-sae), Hwang Shin-hye (Oh Seon-yeong), Bae Chang-ho (Moon Do-seok).

“We live in an age without masterpieces.” So laments Lee Jong-sae (Ahn Sung-ki), the stand-up comedian and aspiring film director who is the central figure of Gagman, the debut film from Lee Myung-se. Jong-sae has spent his life channeling Charlie Chaplin’s The Tramp, down to the signature mustache. He has a grand dream to make a film, and at one point insinuates himself on a movie set, where he collars the director to give him a script, and tells an TV interview crew that he will make his next film with this director. He enlists his barber Do-seok (Bae Chang-ho) to be his lead actor. Do-seok immediately takes to the idea, selling his barbershop to fund the enterprise, trading his business for loud Hawaiian shirts, shades (“Do I look like Jack Nicholson?”), and eyelid surgery. They are soon joined by Seon-yeong (Hwang Shin-hye), who Jong-sae meets when she sits next to him in a movie theater, kissing him with feigned passion in order to hide from some gangsters who are chasing her. Seon-yeong moves in with Jong-sae, and after she finds the machine gun Jong-sae has hidden in his guitar case, conspires with the two men to rob banks to raise the money for their film.

Although Lee’s prodigious visual talents would come to their full flower in later films, especially First Love (1993), and his recent masterpieces Nowhere to Hide (1999) and Duelist (2005), Gagman is a tremendously impressive debut, and Lee's dizzying mixture of dreams, fantasy, pathos, satire, and canny appropriation of film references proved him to be a unique talent right out of the gate. The characters of Jong-sae and Do-seok, according to an interview Lee gave to critic Tony Rayns, were inspired by Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Although Jong-sae, this odd, and perhaps mentally ill, third-rate cabaret comedian tilting at cinematic windmills at first blush seems to be merely a figure of ridicule, this character also elicits sympathy as someone wanting desperately to make a name for himself and matter to the world. This is conveyed by both the witty screenplay by Lee and Bae Chang-ho (a great director in his own right for whom Lee was an assistant), and the mesmerizing performance by Ahn Sung-ki, one of Korea’s finest actors, who truly embodies a character, rather than being simply a collection of quirks and bizarre behavior. His two co-stars are also quite impressive and ably match Ahn note for note. Bae, as Jong-sae’s dimwitted sidekick, and Hwang Shin-hye, as the sexy, devious femme fatale, transform what would be, in lesser hands, merely stock characters into people much deeper and more interesting. All these elements are melded with an arsenal’s worth of cinematic allusions, combining wicked parodies of Korean films (a TV interviewer speaks to an actress who is “known for acting in bed,” and a director who claims his formulaic film as social realism), and appropriations of Hollywood screwball comedy, westerns, and gangster films. Jong-sae evokes not only Charlie Chaplin’s mustache and Little Tramp duck-walk, but in his grasping at fame, Rupert Pupkin in Scorsese’s The King of Comedy. As the three set out to prove Godard’s axiom that all you need to make a film is a girl and a gun, Lee Myung-se uses these materials, and much more, to deliver a great love letter to the movies.

And if you’re in the New York City area, I urge you to see this film on screen at the Imaginasian Theater, where it will screen on January 24, as part of the series “Chungmuro Express: Classic Korean Cinema.” This film series, organized by Korean Cultural Service, will begin with a four-film tribute to actor Ahn Sung-ki. The series’ curator, and my good friend, Hyun-Ock Im, will introduce these screenings and conduct a Q&A afterward. The next screening, on February 28, will be Jeong Ji-young’s Vietnam War drama White Badge. All screenings are free admission and you can RSVP at (212) 759-9550. For more information about Gagman and the film series, see the press release.

Although Lee’s prodigious visual talents would come to their full flower in later films, especially First Love (1993), and his recent masterpieces Nowhere to Hide (1999) and Duelist (2005), Gagman is a tremendously impressive debut, and Lee's dizzying mixture of dreams, fantasy, pathos, satire, and canny appropriation of film references proved him to be a unique talent right out of the gate. The characters of Jong-sae and Do-seok, according to an interview Lee gave to critic Tony Rayns, were inspired by Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Although Jong-sae, this odd, and perhaps mentally ill, third-rate cabaret comedian tilting at cinematic windmills at first blush seems to be merely a figure of ridicule, this character also elicits sympathy as someone wanting desperately to make a name for himself and matter to the world. This is conveyed by both the witty screenplay by Lee and Bae Chang-ho (a great director in his own right for whom Lee was an assistant), and the mesmerizing performance by Ahn Sung-ki, one of Korea’s finest actors, who truly embodies a character, rather than being simply a collection of quirks and bizarre behavior. His two co-stars are also quite impressive and ably match Ahn note for note. Bae, as Jong-sae’s dimwitted sidekick, and Hwang Shin-hye, as the sexy, devious femme fatale, transform what would be, in lesser hands, merely stock characters into people much deeper and more interesting. All these elements are melded with an arsenal’s worth of cinematic allusions, combining wicked parodies of Korean films (a TV interviewer speaks to an actress who is “known for acting in bed,” and a director who claims his formulaic film as social realism), and appropriations of Hollywood screwball comedy, westerns, and gangster films. Jong-sae evokes not only Charlie Chaplin’s mustache and Little Tramp duck-walk, but in his grasping at fame, Rupert Pupkin in Scorsese’s The King of Comedy. As the three set out to prove Godard’s axiom that all you need to make a film is a girl and a gun, Lee Myung-se uses these materials, and much more, to deliver a great love letter to the movies.

And if you’re in the New York City area, I urge you to see this film on screen at the Imaginasian Theater, where it will screen on January 24, as part of the series “Chungmuro Express: Classic Korean Cinema.” This film series, organized by Korean Cultural Service, will begin with a four-film tribute to actor Ahn Sung-ki. The series’ curator, and my good friend, Hyun-Ock Im, will introduce these screenings and conduct a Q&A afterward. The next screening, on February 28, will be Jeong Ji-young’s Vietnam War drama White Badge. All screenings are free admission and you can RSVP at (212) 759-9550. For more information about Gagman and the film series, see the press release.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)