.jpg)

Bashing. 2005. Written and directed by Masahiro Kobayashi. Produced by Masahiro Kobayashi and Naoko Okamura. Cinematography by Koichi Saitoh. Edited by Naoki Kaneko. Music by Hiroshi Hayashi. Sound design by Tatsuo Yokoyama.

Cast: Fusako Urabe (Yuko Takai), Ryuzo Tanaka (Mr. Takai, Her Father), Takayuki Kato (Iwai, Her Lover), Kikujiro Honda (Ueki, Her Father's Boss), Teruyuki Kagawa (The Hotel Owner), Nene Otsuka (The Stepmother).

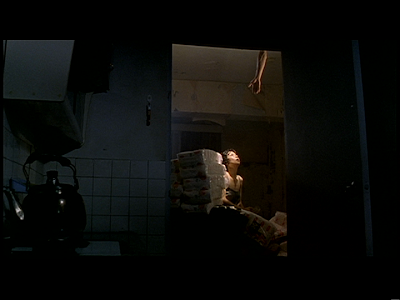

Masahiro Kobayashi's Bashing takes as its inspiration the ostracism experienced by Japanese humanitarian workers in Iraq after surviving kidnapping there. The film's protagonist, Yuko (played with quiet intensity by Fusako Urabe), an aid worker recently returned after being freed, is a withdrawn and sullen woman plagued by constant harassment by strangers and threatening anonymous phone calls at home. As the film begins, Yuko in short order loses her job as a hotel maid, and her boyfriend coldly rejects her, astonishingly telling her that if she had been killed, she would have been a hero, but having returned alive, she is now simply "an embarrassment to all Japan." Yuko's father (Ryuzo Tanaka) also loses his factory job of 30 years due to the negative attention his daughter’s return has caused. The film, set in the cold landscape of Hokkaido, hones in with laser focus on Yuko's oppression, aided by the roving, stalking camerawork that at times recalls the Dardenne brothers. Minute, repetitious details of her drab existence dominate: trudging up the steps to the apartment where she lives with her parents; making her soup order at the local minimart; lying in her bed, curled up in a fetal position; and staring wistfully at the ocean, contemplating a return to the place that, however dangerous, was the only place she felt useful and loved. Interestingly enough, the film, as harsh as it is in condemning Yuko's treatment by society, does not make her simply a helpless victim. Yuko is not entirely sympathetic. She often walls herself off even from those closest to her, especially her parents, who, unlike everyone else, are mostly supportive of her work. It is also clear that her aid work is not entirely altruistic; Iraq was an escape from a country where she felt a failure, and a place where she was adored by the children she worked with and fed sweets.

Kobayashi's film is a rather blunt but compelling critique of some of the intolerant and cruel elements of Japanese society. The film, other than an opening statement saying that the film was based on true events, does not attempt to put its scenario in a larger context (Iraq is not mentioned at all), which may make the film's oppressive sense of claustrophobia seem irrational and farfetched. Being aware, for example, that in 2004 (when the true events that Bashing takes as its inspiration occurred) then-Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi made public statements blaming the hostages for their predicament, greatly enhances one's understanding of the situation the film presents. Nevertheless, Kobayashi, aided by Fusako Urabe's complex performance, and strong work by the supporting cast, intensely portrays the persecution suffered, especially in rigid and moralistic societies, by those who step outside of that society's constricted roles.

Bashing is available on DVD from Amazon.

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png) The Hole, despite the pre-millennium tension that permeates it, and the familiar crying and despair that exists in its world, is Tsai’s most light-hearted and hopeful film. And although Tsai would disagree, a shaft of light suggesting a passage to heaven, a proffered glass of water, an outstretched hand, and a final love song from Grace Chang, all lead to what is as close to a happy ending as you’ll find in Tsai Ming-liang’s oeuvre.

The Hole, despite the pre-millennium tension that permeates it, and the familiar crying and despair that exists in its world, is Tsai’s most light-hearted and hopeful film. And although Tsai would disagree, a shaft of light suggesting a passage to heaven, a proffered glass of water, an outstretched hand, and a final love song from Grace Chang, all lead to what is as close to a happy ending as you’ll find in Tsai Ming-liang’s oeuvre..png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)