Hunger. 2008. Directed by Steve McQueen. Written by Enda Walsh and Steve McQueen. Produced by Laura Hastings-Smith and Robin Gutch. Cinematography by Sean Bobbitt. Edited by Joe Walker. Production design by Tom McCullagh. Music by David Holmes and Leo Abrahams. Sound design by Paul Davies. Costume design by Anushia Nieradzik.

Cast: Michael Fassbender (Bobby Sands), Brian Milligan (Davey Gillen), Liam McMahon (Gerry Campbell), Stuart Graham (Raymond Lohan), Liam Cunningham (Father Dominic Moran), Laine Megaw (Raymond's Wife), Karen Hassan (Gerry's Girlfriend), Frank McCusker (The Governor), Helen Madden (Mrs. Sands), Des McAleer (Mr. Sands), Ciaran Flynn (Twelve Year Old Bobby).

Turner Prize-winning artist Steve McQueen’s impressive feature debut Hunger, screening at this year's New York Film Festival, is not your normal biopic. And that’s a very good thing. McQueen’s film, which won the Camera d'Or (best first film) at this year's Cannes Film Festival, examines the final days of IRA activist and political prisoner Bobby Sands, as he slowly perished from a 66-day hunger strike in 1981, a pivotal event of the “Troubles,” the protracted war involving Northern Ireland’s struggles against the British for independence. After the briefest of opening titles to quickly set the historical background, it becomes immediately clear that McQueen isn’t aiming for the outraged agitprop of, for example, Ken Loach, who also tackled this conflict in his film The Wind That Shakes the Barley. Politics obviously interests McQueen less than the human story being told here. McQueen channels his prodigious visual skills honed from his previous video artworks to astound and assault us with indelible images edited with a nearly unbearable razor’s edge. The film begins not with its putative subject Bobby Sands (he doesn’t even appear until a third of the way into the film), but with prison guard Raymond Lohan (Stuart Graham), as he peers with haunted eyes into a mirror, exchanges fraught glances with his fearful wife, washes his bloody knuckles in a sink (the result of years of beating prisoners), and, after carefully checking his car for hidden explosives, drives off to work. Once there, Raymond wanders in a permanent daze, separating himself from the garrulous chatter of his colleagues, and wanders off by himself to have a smoke in the snowy cold.

Much of McQueen’s video art are silent works, and in “Deadpan,” one of his most famous pieces, the artist himself restages a scene from one of Buster Keaton’s films by having the façade of a house falls on top of him, McQueen preserved from harm because he is standing where an open doorway falls. “Deadpan” directly addresses McQueen’s artistic debt to silent cinema, and this style carries over to Hunger. McQueen almost entirely dispenses with dialog in this film, with the major exception of a key scene in the middle of the film (more about that later). Sound and image, especially sound, are given primacy here. The film’s main setting is the notorious Maze prison, where the imprisoned IRA members were kept. The visceral images, mostly involving bodily fluids – blood, urine, excrement – are rendered with stark, tactile immediacy, rubbing the viewers’ faces into the muck and grime of the prison, everything beautifully composed but no less difficult to watch. This filth is directly connected to the main political grievances of the prisoners. Before the hunger strikes (there were actually two major ones; the one depicted in the film was the second and more effective) were two other protests, known as the “blanket” and “no wash” protests. The blanket protest stemmed from the stripping from the prisoners of special political status, which recognized that they were different from common criminals and more akin to prisoners of war, which gave them such rights as free assembly, exemption from work detail, and the right to wear civilian clothes instead of prison uniforms. In protest to the elimination of these rights, which was part of Margaret Thatcher’s unrelentingly hard-line methods, the inmates refused to wear any clothes and would only take blankets to cover themselves. Prison guards retaliated against this action by not allowing them to use the toilets, which led to the “no wash” protests, where the prisoners refused to bathe themselves and urinated and defecated inside their cells, smearing the excrement on the walls. In Hunger the camera lingers on long shots of the cells caked with feces, in one case arranged in a very artful bull’s-eye pattern.

The impact of these protests are given form and character in Hunger in the guise of two prisoners we follow in the film’s early scenes. Davey Gillen (Brian Milligan), a new prisoner, is shown the ropes by cellmate Gerry Campbell (Liam MacMahon), and through their experience, we are witness to the excruciating details of brutal life in the prison, in the scenes where the prisoners are forcibly removed from their cells and washed down and their hair savagely cut, with bloody chunks of scalp taken off with it. They pass messages and other items with visitors from outside the prison by hiding and transporting them through various bodily orifices. This illustrates the film’s major theme: the body, specifically the male body, as the vessel and site of resistance to authority. Often stripped naked, beaten and dragged through the corridors by the prison guards, their bodies are literally all they have, and the hunger strike becomes the ultimate form of self-sacrifice and martyrdom to their cause. These methods recall such disparate phenomena as those who immolated themselves to protest the Vietnam War, and (for of course very different reasons) present day suicide bombers. Considering that McQueen and his co-screenwriter Enda Walsh began writing their script well before the Iraq War, Guantanamo Bay, and Abu Ghraib, the present-day parallels are even more remarkably prescient.

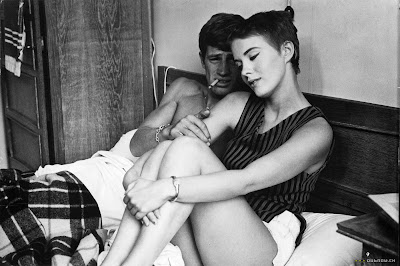

After following the two prisoners, we are introduced rather offhandedly to Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender), as he is visited by his parents. This serves to ground him and counteract against seeing him as a special person and reinforce the fact that as celebrated (and notorious) as Sands was, he was part of a movement that was much larger than one person. Bobby Sands also, as with the first two prisoners in the film, is subjected to prison brutality, undergoing a vicious cavity search by the guards. Yet there is something singular about Sands, and he does consciously see himself as a symbol. The rest of the film demonstrates this, and quite surprisingly, it reveals itself as very Catholic work, and Sands emerges as a Christ figure. An irreverent, indeed sacrilegious one, to be sure (he rips up his copy of the Bible to use as rolling papers for his cigarettes), but a Christ figure nonetheless. The suffering and physical deterioration of Sands’ hunger strike render this in intricate detail, the sores on his skin looking like nothing less than stigmata.

Sands directly argues the rationale behind his decision to go on the hunger strike in an extraordinary scene in the center of the film, in which he debates a visiting priest (Liam Cunningham) over the wisdom and effectiveness of the strike. After virtually no dialog up to that point, we are confronted with an avalanche of speech as the two men verbally parry in their dialectical debate. Sands is uncompromising in his refusal to negotiate or settle for less than the full reinstatement of their special political status, while the priests stresses the importance of compromise. Their conversation is filmed in a side view of the two men in profile, in a static shot that runs about ten minutes. It represents a breather from the stark violence and an opportunity for the viewer to reflect on the greater meaning of this struggle, and indeed, what it really means to die for a cause.

Unconvinced by the priest’s arguments, Sands goes through with the hunger strike, in which nine other prisoners died. The film focuses on Sands, as he slowly deteriorates, eventually unable to get around without help, as his vision and hearing fail him, and as he begins seeing visions of himself as a young boy appear to him. Again like Christ, he resists the temptations put before him, this time of the plates of food that loom before the camera, as Sands turns away, hurtling toward certain death with steel-like resolve. As he dies, Sands’ image is superimposed with a flock of birds, representing the freedom that death has given him, a rather trite and clichéd image that is the film’s only misstep.

While the sight of a man wasting away from starvation is no one’s idea of a fun night out at the movies, Hunger rewards those able to endure the extreme imagery with a compelling artistic vision. McQueen’s images (aided by Sean Bobbitt’s precisely rendered cinematography) have a cold beauty that forms a striking contrast to the grimness (and griminess) of their content. McQueen, unlike other visual artists transitioning to cinema, has a sure hand with the form, especially in working with his actors. Michael Fassbender (best known to U.S. audiences from Zack Snyder’s 300) as Sands especially impresses in his scene with the priest and in navigating the physical challenges of his role (he clearly actually fasted for the film’s latter scenes).

Hunger screens on September 27 and 28 at the New York Film Festival, and will open in early 2009.